Growing watermelons in Indiana isn’t always easy if you have cucumber beetles and spider mites. These pests are some of the most damaging to Midwest cucurbits and are commonly managed with a combination of insecticides and miticides. Unfortunately, chemical management for one pest could interfere with control of another pest. For example, spider mite outbreaks have been historically associated with the use of broad-spectrum insecticides like pyrethroids and neonicotinoids. This suggests that aggressive cucumber beetle management could be indirectly triggering spider mite outbreaks, but this relationship has not previously been tested.

Indiana melon growers also extensively use grass cover crops, such as cereal rye, to act as a windbreak and protect seedlings from sand-blasting damage. However, during conversations with cucurbit growers, we repeatedly heard anecdotal reports that spider mite outbreaks are caused by rye strips in their fields. The idea is that spider mites use it as a “green bridge” to build up large early-season populations that then colonize the crop starting in July. Rye is seeded in the fall, interspersed with watermelon rows (typically at a ratio of 3 watermelon rows: 1 rye row), placing it in close proximity to the crop where spider mites can rapidly colonize. However, to our knowledge, no one has ever experimentally tested the impact of rye use on spider mite densities in cucurbits.

To test the combined impacts of insecticide use and rye cover crop on spider mites in watermelon, we conducted a trial in 2023 at one Purdue Agricultural Center (TPAC) and then repeated this trial in 2024 at three PACs across Indiana (TPAC, SWPAC and SEPAC). We compared two insecticide programs: 1) a standard insecticide program and 2) an integrated pest management (IPM) program that followed economic threshold-based recommendations. The standard program consisted of an initial imidacloprid application at planting (same active ingredient used in Admire Pro) followed every 2 weeks by foliar pyrethroid applications (same active ingredient used in products like Pounce or Warrior II). In the threshold IPM program, we applied acetamiprid (e.g., Assail) when beetles exceeded a threshold density of five per plant. However, that only happened once in 2023, while no insecticides were needed in 2024. The use of rye cover crop had two levels: present or absent. The combination of insecticide and rye resulted in four treatments:

- standard insecticide + rye presence

- standard insecticide + rye absence

- threshold insecticide + rye presence

- threshold insecticide + rye absence

We randomly allocated each treatment to plots and replicated them five times per year-site (Figure 1), resulting in 20 plot replicates for each of the four treatments.

Figure 1. Example of one plot (July 2024, SWPAC) including the 20 plots. We highlighted two plots (dashed polygons), one with rye absent (left in blue) and another with rye present (right in yellow) (Photo by Zeus Mateos ).

We released ~1,600 spider mites per plot 3-4 times to ensure high infestation levels (Figure 2). We then visually scouted all plots weekly from planting to harvest, counting cucumber beetles and natural enemies per plant, and spider mites per leaf due to their smaller size. We kept track of natural enemies since insecticide-induced spider mite outbreaks are thought to be caused by disrupting their natural control by beneficial insects such as ladybugs.

Figure 2. We evenly distributed and placed infested bean leaves in direct contact with the watermelon leaves (June 2024) (Photo by Zeus Mateos).

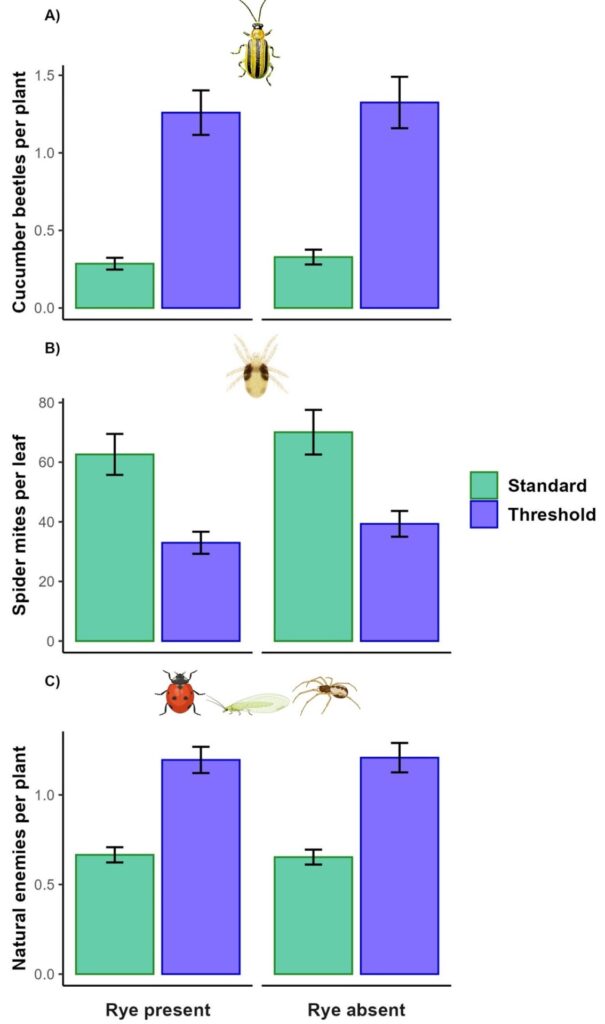

Among the natural enemies, spiders were the most abundant group at 50% of observations, followed by ladybugs (21%) and lacewings (13%). Both pests (Figures 3A, B) and natural enemies (Figure 3C) were affected by the insecticide programs but not by the presence of rye (Figure 4). Cucumber beetles and natural enemies were more abundant in the threshold IPM program, while spider mites were more often found in the standard insecticide program. The presence of rye did not affect either pests or natural enemies.

Figure 3A. Striped cucumber beetles on a watermelon leaf with a close-up of a beetle on a flower (Photo by Zeus Mateos).

Figure 3B. Watermelon plants infested with spider mites, with a close-up of spider mites on a leaf (Photo by Zeus Mateos).

Figure 3C. natural enemies, including a spider (top left), a ladybug (bottom left) and a lacewing larva feeding on an aphid (right) (Photo by Zeus Mateos).

These data strongly implicate broad-spectrum insecticide use targeting cucumber beetles is triggering spider mite outbreaks in watermelon fields (Figure 4). Thus, in fields with a history of spider mite problems, growers should limit insecticide applications and prioritize reduced-risk insecticides that avoid disrupting the beneficial insect community. This is a particularly important consideration given grower-reported cases of miticide resistance developing in recent years for Indiana spider mite populations.

Figure 4. Mean numbers of A) cucumber beetles per plant B) spider mites per leaf C) and natural enemies per plant according to insecticide (standard vs. threshold) and rye cover crop (presence vs. absence).

Importantly, our results also show that spider mites do not seem to use rye as a bridge to move into the crop. Even though we infested the rye, we never observed spider mites reproducing there, suggesting that it may not be a preferable host plant for this pest. We also observed the same outcome when trying to artificially inoculate rye plants with spider mites in the lab (i.e., establishment and reproduction were always low).

Overall, our results emphasize the importance of adopting IPM to manage primary pests, minimize secondary pest outbreaks, and protect natural enemies and other beneficial insects by providing free ecosystem services such as biocontrol and pollination.

We want to thank PAC managers Chloe Richard (TPAC), Dennis Nowaskie (SWPAC), Joel Wahlman (SEPAC), and their crews for setting and managing the plots and the techs, staff, and students who helped collect data and harvest.