Seedless watermelons are extremely dependent on pollinators for yield. A pollinator, typically a bee, has to first visit a male flower from a pollinizer plant (pollen donor) and then deposit the pollen on a female flower from the seedless plant. That pollinated female flower will become a seedless watermelon fruit. This pollen-transfer job can be done for free by wild bees, but because watermelon fields can be 100+ acres, growers rent honey bee hives from beekeepers to ensure there are enough pollinators that can visit all the flowers. Honey bees are the most widespread pollinator in the world, but they aren’t very efficient and don’t forage when it’s too cold, too hot, windy, or rainy. That’s why some growers supplement their fields with a second managed pollinator, the common eastern bumble bee (Figure 1). Bumble bees are known to be better foragers in adverse weather conditions and growers invest a lot of money in bumble bee hives. However, due to their cost and the fact that bumble bees are a relatively new input to the production system (compared with honey bees that have been used for a long time), growers have wondered whether managed bumble bees are worth the investment.

Figure 1. A commercial watermelon field with managed bumble bee hives and the close-up of a common eastern bumble bee visiting a watermelon flower (Photos by Zeus Mateos).

To investigate the role of managed bumble bees and provide growers with effective pollinator management recommendations, we combined field observations with experiments in six commercial seedless watermelon fields in Southwestern Indiana in summer 2025. All fields were stocked with honey bee hives, but only three of the fields were additionally stocked with bumble bee hives, which we deployed near one of the field edges.

We first conducted field observations (June-August) by counting the number of watermelon flowers visited by bumble bees, honey bees, and wild bees, and how many flowers they visited per minute. We did these observations i) in the field edge (next to the bumble bee hives when present) and ii) in the field center (>600 ft into the fields). Secondly, we sprayed fluorescent powder into the bumble bee hives to cover the bumble bees with it. These bumble bees would leave powder traces on the watermelon flowers after a visit. We then examined >1,000 flowers in fields with or without managed bumble bee hives and recorded how many of those flowers had fluorescent powder traces. This technique was used to provide direct evidence of flower visits by managed bees, which is especially important since wild bumble bees also forage in these fields, and it can otherwise be hard to differentiate the contribution from managed versus wild bumble bees in fields. Finally, we harvested pollen loads from bumble bees and analyzed the percentage of pollen grains that belonged to watermelon, across 16,500 pollen grains!

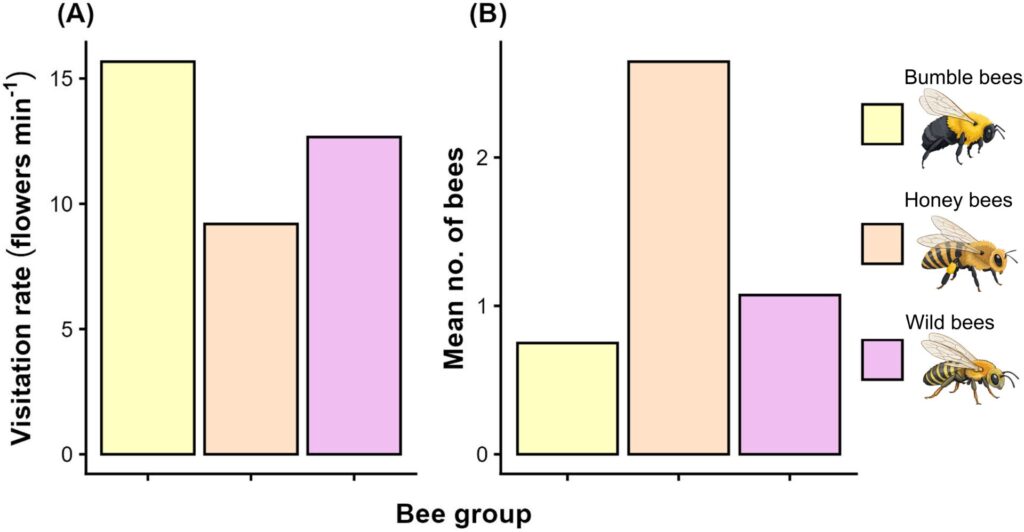

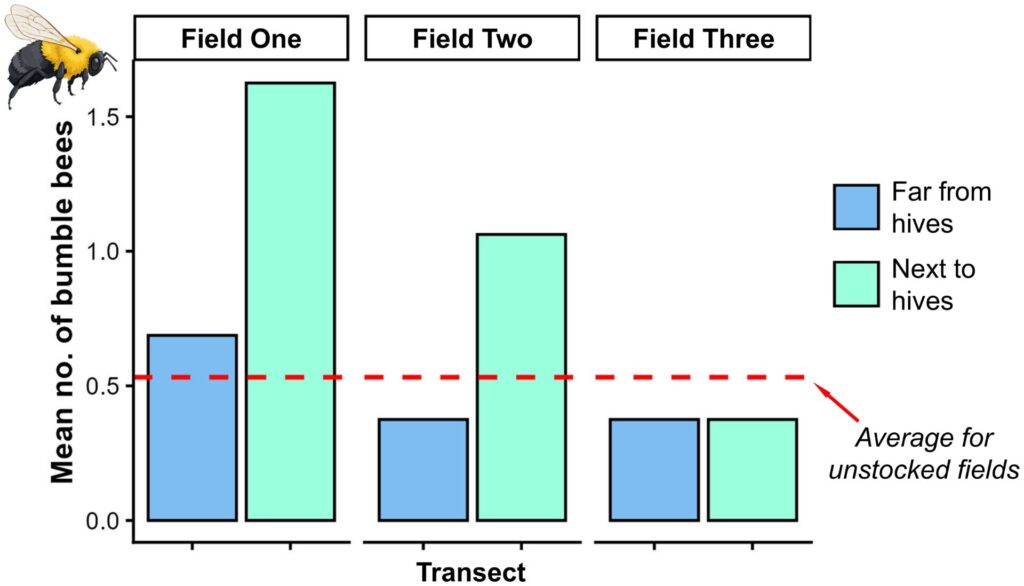

Our field observations showed that bumble bees are the most efficient bees, as they visit more flowers per minute (~15 flowers min-1), although wild bees are also better pollinators than honey bees (Figure 2A). Keep in mind that this only tracks the efficiency of individual bees and does not account for numerical differences among groups (i.e., some bees can be highly efficient as individual foragers while not being numerous enough to pollinate the crop). However, despite being the most efficient, bumble bees were not frequently recorded; they were the least observed compared to honey bees or wild bees (Figure 2B). Supplementing fields with bumble bees generally increased their visitation rate to watermelon flowers, although the magnitude of this increase varied across fields (Figure 3). Importantly, the boost in bumble bee numbers from supplementation was only observed locally, close to the hives and was not apparent far from the hives in the center of the field.

Figure 2. Mean number of A) flowers visited per minute and B) individual bees per 5-min observation according to bee group (bumble bees, honey bees and wild solitary bees) across all fields.

Figure 3. Mean number of bumble bees recorded per 5-min observation in transects far from hives or next to hives in each of the three fields that were stocked with managed bumble bees. The red dashed line indicates the mean number of wild bumble bees recorded across the non-bumble bee-stocked fields.

The experiment with fluorescent powder showed somewhat similar patterns. No traces were found in any of the flowers from fields without managed bumble bees. Whereas in the fields supplied with bumble bees, 2.2% of the flowers around the bumble bee hives had fluorescent powder traces. The pollen composition of bumble bee pollen loads revealed that less than 1% of the pollen collected belonged to watermelon, while the vast majority came from white and red clover. Bumble bees clearly love legumes!

Collectively, our data suggest that supplying watermelon fields with managed bumble bees may not significantly increase the number of bumble bees recorded on watermelon flowers and consequently may not contribute to improving yield profitability. Bumble bees were only recorded visiting flowers close to the hives, likely because those flowers were more accessible, but they didn’t travel far into the field, instead preferring other floral resources such as legumes over watermelon. Thus, watermelon growers who wish to continue using bumble bees should consider distributing the hives throughout the field at regular distances, and while clover and other flowering weeds can boost wild bees (including wild bumble bees), clover might also draw managed bumble bees away from watermelon flowers.

In our study, while yields were similar across fields, we couldn’t adequately compare these data for several reasons, i.e., lack of evidence for a yield increase with managed bumble bees. First, we used only six fields: three with and three without managed bumble bees. Differences in management practices and watermelon varieties can substantially affect yields. Secondly, we used a lower bumble bee hive rate compared to standard commercial rates (which vary from 0.5 to 1 hive per acre), thus minimizing the potential to detect an effect on yields. Finally, our study was done in a single year, and multiple years are needed to explore different weather conditions. The 2025 season, while wet, wasn’t especially cold or hot. Weather can be adverse in future years, and bumble bee presence may help secure yields if honey bees don’t visit flowers. Consequently, future studies should account for all these limitations to properly assess the impacts of supplementation on yield.

If hive costs are a concern, we recommend taking advantage of the diversity of free, wild bees inhabiting fields by minimizing and timing insecticide applications to avoid non-target effects and using more pollinator-friendly products. Habitat support, such as flowering cover crops, can also help increase wild bee numbers.

We want to thank the grower collaborators and technicians who helped with the fluorescent assay and pollen analysis.