Description

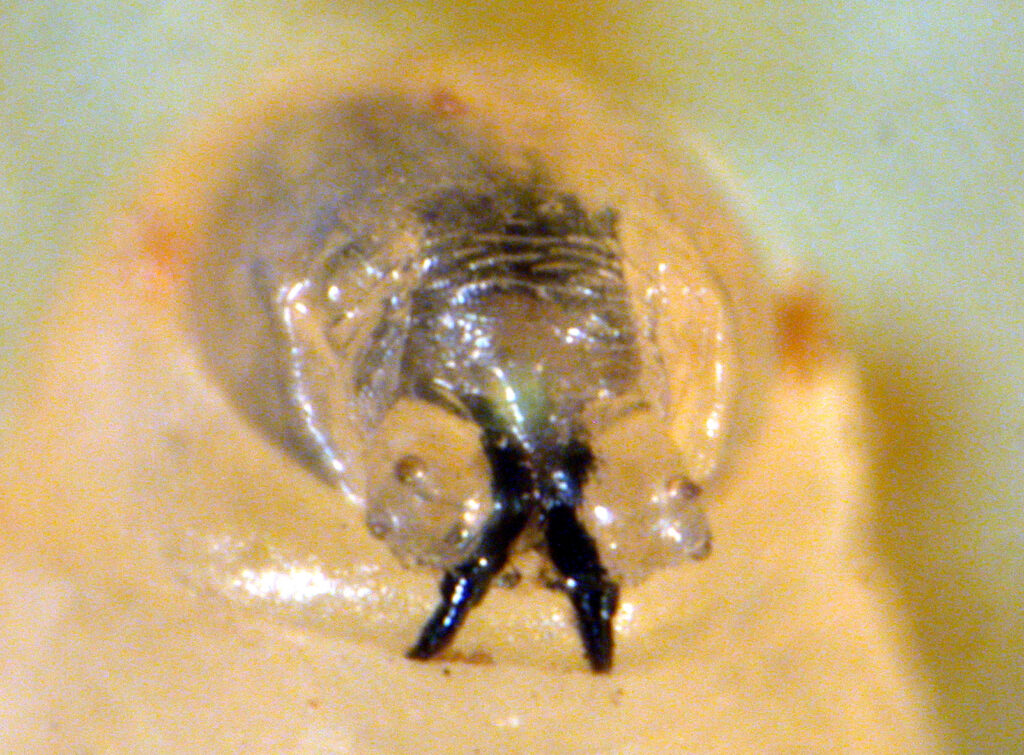

The seedcorn maggot, or Delia platura, is a frequent pest in the Anthomyiidae family that can affect both specialty and agronomic crops, including corn, melons, onions, pumpkins, and many others. The larvae, or maggots, of this species damage the crops. The larvae tend to be white or translucent in color, about 1/4 inch long, with a black hook-shaped mouthpart on one end (Figure 1). The pupae of this species are small brown cases that are about 1/4 inch long, usually resembling a wheat seed (Figure 2). The adults of this species are typically brown or grey in color, roughly 1/5 inch long, and look like a smaller version of a house fly (Figure 2).

Life Cycle

Seedcorn maggots overwinter as pupae in the soil, emerge as adults, and mate in early spring. The females will then lay their eggs in the soil, where they will hatch within 2-5 days. Afterwards, the larvae will then feed for about 2-3 weeks before pupating, where they will remain for 1-2 weeks in the soil before hatching. Typically, you will find the pupae in the dirt and roots surrounding the plant they fed on; however, the pupae can still be found inside the plant, living in the cavity it made during larval feeding.

Due to their short development time, you can expect 3-5 generations of seedcorn maggot a year. Luckily for us, we have the capacity to monitor and track these generations through a tool that we refer to as growing degree days. Knowing the temperature at which the fly is biologically active and developing, and the length of time at the specified temperature that it takes to complete each step of its development, we can track and predict the population cycles by following local weather conditions. For seedcorn maggot, we use the base temperature of 39°F to calculate the degree-day development of this insect.

Damage

Seedcorn maggot is a particularly detrimental pest as it feeds on the seeds and seedlings of plants. Typically, this damage is hard to catch at the onset as it occurs underground; however, the plant will typically begin showing signs of infestation soon after the larvae begin feeding. This can look like wilting (Figure 3) and necrosis near the base of the plant. Upon closer observation of the damage, one would notice heavy discoloration at the base of the plant with little to no resistance when gently squeezed. Upon breaking open the plant, one would notice a hollow cavity coated in a slime-like substance with the maggots moving around and the root structures greatly reduced or completely removed as a result of their feeding (Figures 4-5).

Management

Unfortunately, there are no effective rescue treatments once a crop has been attacked by seedcorn maggot. The best management strategies are preventative. This includes monitoring the emergence of seedcorn maggot using tools developed for growing degree day calculations and planting crops at times that avoid their peak activity.

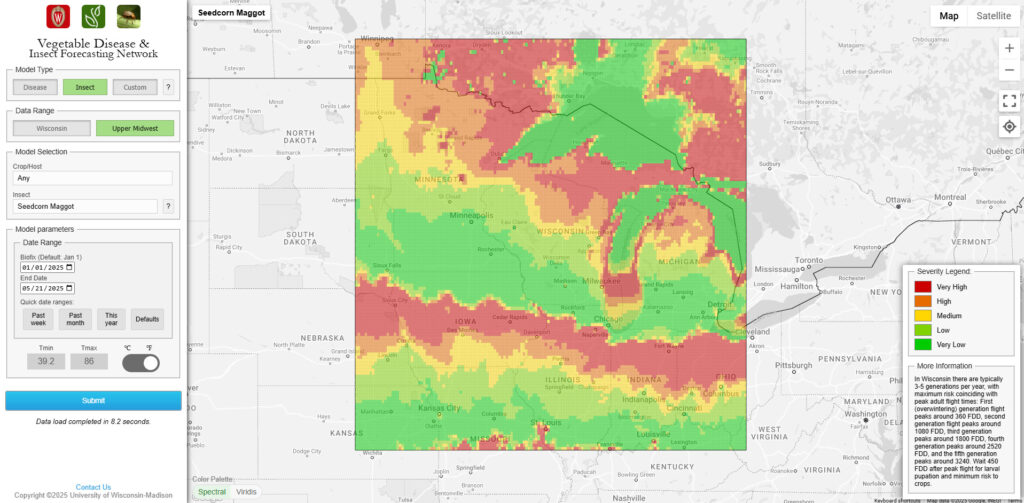

The VDIFN model is one tool that can be effectively utilized to monitor the development of seedcorn maggot, among other pests. This model displays the accumulation of GDD and associated risk of pest pressure in each region of the map, based on temperature data (Figure 6). Using this tool at the time of writing, we can see that here in Indiana, the northern portion of the state is experiencing the peak emergence of the second generation of seedcorn maggot, while in the south, development of the third is underway, and the current risk to planting/seedlings is low.

Figure 6. Screenshot of VDIFN tool showing current (5/22/2025) development of seedcorn maggot based on weather data.

The utility of this model is the first step in successful IPM for seedcorn maggots (and any other pest for which it can provide predictive models). You should consult the model first to see if you are at risk or not, then consider the history of the field you are planting, the susceptibility of the crop, and weigh the cost of an insecticide treatment as a prevention with the risk of encountering the pest during the most susceptible point of crop development.

Spring planting is the most susceptible because if conditions do not favor rapid growth of the plant (i.e., cold and wet), the insect has the advantage and can still feed. High residues of organic matter are attractive to adult flies for egg laying. If your site has a history of seedcorn maggot pressure and you are planting into soil with high organic matter or cover crop residues, you can consult the Midwest Vegetable Production Guide for guidance on pesticides that can be used at or near planting to prevent damage. During later times in the season, the pest is present, but conditions are typically more favorable for vigorous plant growth, and your seedlings or young transplants can compensate for some root feeding by outgrowing the threat.

Have fun with the seedcorn maggot GDD risk tool and take some time to explore other pests that can be monitored using the same methods! It can save you time scouting and money related to costly pesticide applications that may not be needed.